I cannot celebrate this Independence Day in a spirit of joy over “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Yet I feel in this time that the clarity we see these days for America’s faults is now more than ever balanced by America’s possibility, that continuing yet unfulfilled promise of equality.

That possibility was born on the Third of July. This year, I will celebrate it and mourn the Fourth.

The Third of July birthday of which I speak was July 3, 1863. That day ended the Battle of Gettysburg. It saw the repulse of Pickett’s Charge, the hamstringing of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, and the beginning of the end of Robert E. Lee’s rebellion. July 3 signaled the long march to the eventual ruin of slavery and the Confederacy.

Admittedly, the Confederacy of the mind won the Jim Crow peace. This “Lost Cause” resisted equality and civil rights for nearly a century after Appomattox (and that same resistance under the banner of the Confederate battle flag is invoked every time the flag’s removal is protested). But the actual Civil War’s end, and the victory of the idea of equality, began at Gettysburg.

Indeed, in reflecting on the underlying meaning of Gettysburg in his famous November 1863 address, President Abraham Lincoln saw the battle as the test of whether American democracy based on rhetoric of equality could survive civil war. In his famous speech, he hoped

that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

That cause, the New Birth of Freedom, promised an America that laid stock in Lincoln’s great cause of abolishing slavery and restoring union (even despite Lincoln’s own slow realization of the former). The bullets and blood of Gettysburg set in motion the ultimate Reconstruction of the US Constitution that promised an equal protection of the laws for all persons in the United States without yolk of slavery or differentiation based on status or race.

Unlike the America of the Founders, that promised United States actually includes me as a free Black man equal to all other men and women. It is that New Birth of Freedom that I prefer to celebrate through commemorating the victory of Gettysburg and the demise and fall of the Confederacy. For that victory sowed the seeds of a Union more perfect than the one of 1789.

This promise is an answer to African-American orator Frederick Douglass’s question, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” His Independence Day 1852 oration held a mirror to a white supremacist America that would enslave his body yet celebrate liberty:

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.

We appreciate Douglass’s assertions even more today. Indeed, the irony of Thomas Jefferson’s appeal to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is clear when we recognize that he echoed John Locke, who pointed to “life, liberty, and property,” and thus we can read Jefferson’s rhetoric (as forced by Southern slaveholders) as a protection of his property—including his slaves. Moreover, the signers of the Declaration of Independence used their eloquent call for liberty to shroud their tax revolt which in a sense sought to reapportion more of the benefits of the transatlantic slave trade to themselves. And it is to appreciate that the original pro-slavery American constitution set the stage for our arguments about race today.

We appreciate Douglass’s assertions even more today. Indeed, the irony of Thomas Jefferson’s appeal to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is clear when we recognize that he echoed John Locke, who pointed to “life, liberty, and property,” and thus we can read Jefferson’s rhetoric (as forced by Southern slaveholders) as a protection of his property—including his slaves. Moreover, the signers of the Declaration of Independence used their eloquent call for liberty to shroud their tax revolt which in a sense sought to reapportion more of the benefits of the transatlantic slave trade to themselves. And it is to appreciate that the original pro-slavery American constitution set the stage for our arguments about race today.

I like Douglass must ultimately morn. Even in this 244th year of the United States, Lincoln’s promised freedom and the reconstructed constitutionalism which should have followed remains desperately under fulfilled. Antiblackness still pervades and perverts promised liberty for all.

My life still remains at greater risk than a white life at police stop. I mourn for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, and how their deaths are symbols of the many thousands gone because of extremist police violence against people of color (who’s origins are inextricably tied to slavery). To speak their names is to invoke the sign and signal of an America still addicted to anti-Black police violence. For me to invoke their memories is to remember my own life has a target on it. And so I mourn.

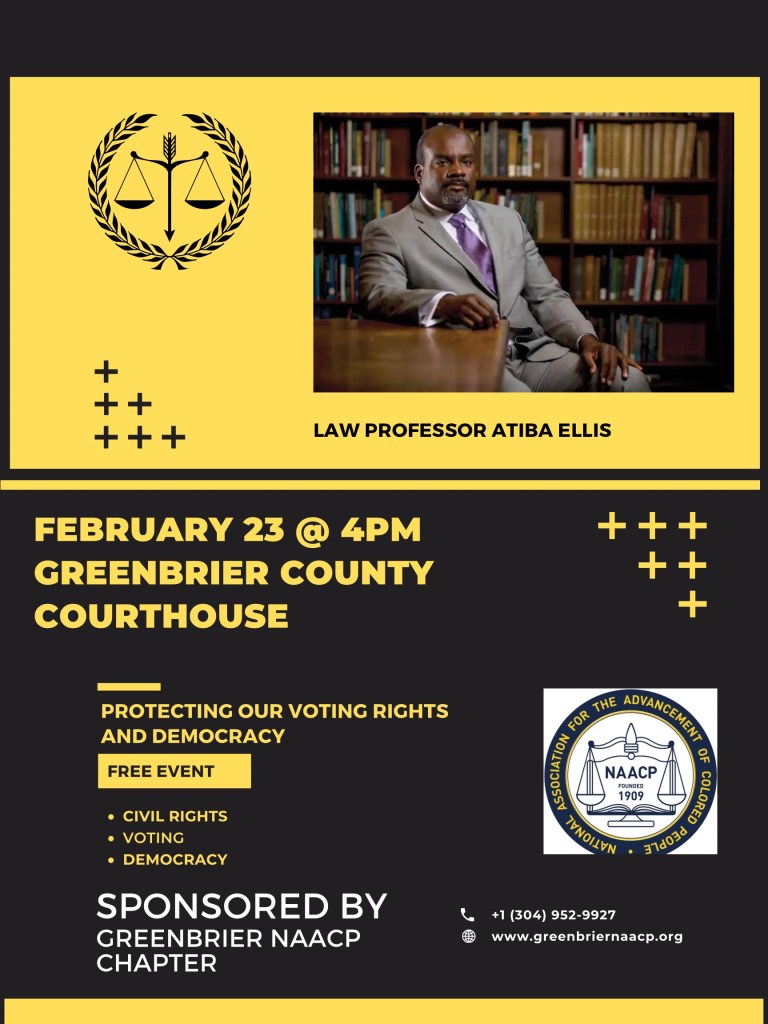

I mourn because my vote is devalued because of the caprice of those who suppress the votes of Black, Latinx, and poor people. I mourn for the racial wealth gap, the school-to-prison pipeline, and the fact that Black and Brown bodies suffer and die more from COVID-19.

I cannot but join Douglass in saying that an America that claims liberty and justice for all, as measured by its progress in all these structures of racism from the Founding to the present, may have improved since 1863, but ultimately America (to date) remains “false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.” And thus, on this eve of Independence, the contradiction between the promise and the reality of America is clear. And I wonder whether the promise of overthrowing racial oppression once and for all is true.

But rather than despair, I, like Douglass, would say, “notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.” Indeed, I am heartened by the destruction of communal symbols of racism and white supremacy—blackface, appropriated black icons, and propagandistic Confederate statues, to name a few—and I express my hope that further mindful erasure of allegiances to white supremacy through democratic deliberation continue.

But for a Fourth of July that is more joy than pain for me, the Reconstruction must actually be completed. The promise of the Third of July must be fulfilled by transforming the structures that perpetuate racist effects (even without any racist intent). That includes, among other things, reinvented policing, reimagined democracy, and a revision of the structures and ideology that perpetuate the New Jim Crow. Government of the people must protect and value all the people.

Until then, “this Fourth of July is yours, not mine.”

We appreciate Douglass’s assertions even more today. Indeed, the irony of Thomas Jefferson’s appeal to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is clear when we recognize that he

We appreciate Douglass’s assertions even more today. Indeed, the irony of Thomas Jefferson’s appeal to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is clear when we recognize that he

First, the Court held that the power to regulate individuals and corporations fell to the states, not the federal government. Second, to the extent Congress passed the Act under its Fourteenth Amendment authority, the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment was limited to regulating actions by states and not private actors (a doctrine that still holds today). Finally, the Court interpreted the Thirteenth Amendment, meant to remedy the badges and incidents of slavery, as only allowing Congress to abolish denials of legal rights extending from past slavery.

First, the Court held that the power to regulate individuals and corporations fell to the states, not the federal government. Second, to the extent Congress passed the Act under its Fourteenth Amendment authority, the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment was limited to regulating actions by states and not private actors (a doctrine that still holds today). Finally, the Court interpreted the Thirteenth Amendment, meant to remedy the badges and incidents of slavery, as only allowing Congress to abolish denials of legal rights extending from past slavery.